Introduction

I was recently exploring the idea of adding some metrics to my personal project. My use case was simple: I wanted to let users track the number of packets processed by each of their firewall rules over time. All I needed was a graph that showed the daily, weekly, and monthly trends of the number of packets processed by each rule.

Initial Exploration

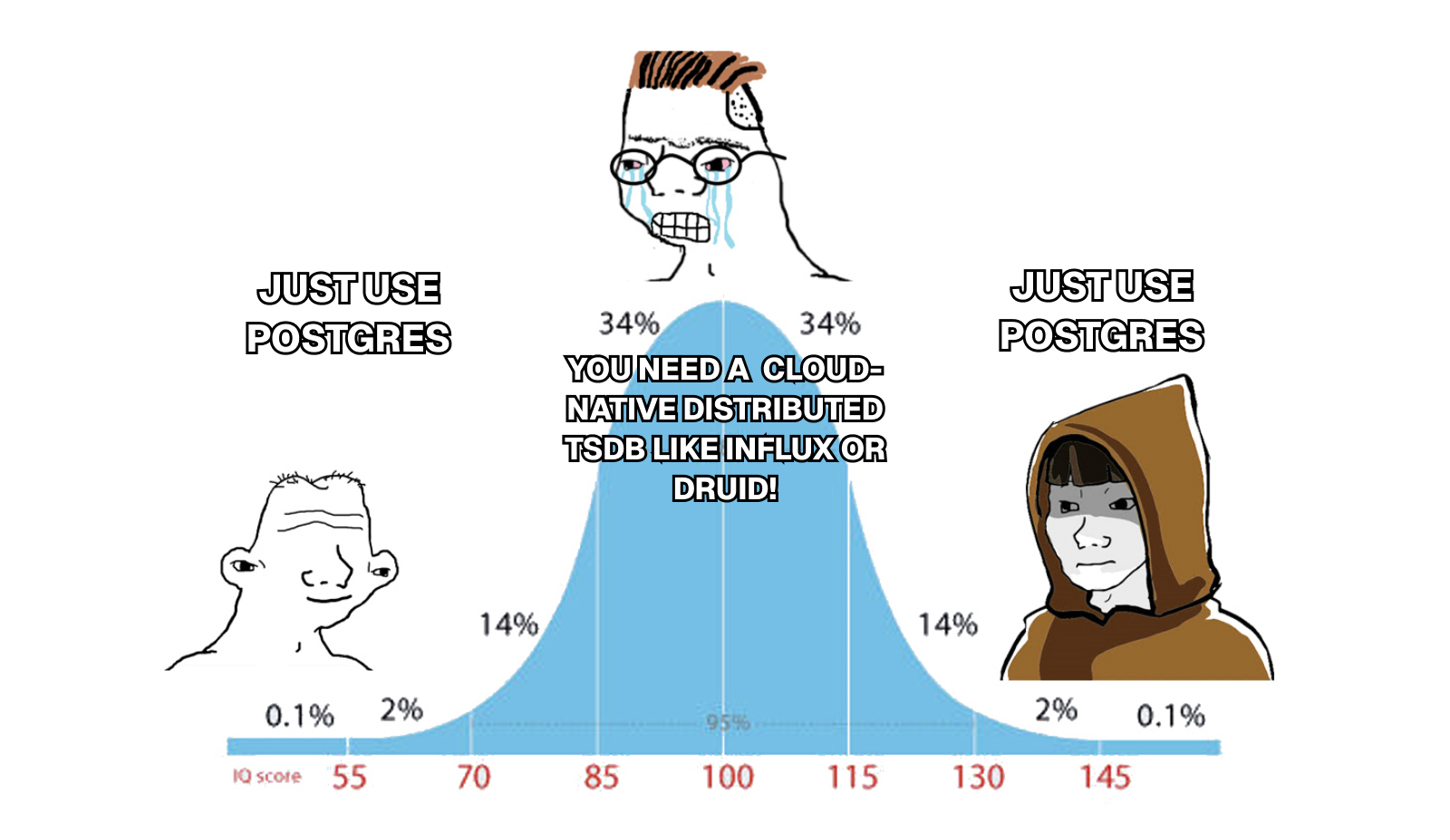

As I was researching my options in terms of databases, I quickly came to the conclusion that most of the time series databases out there have limited licensing options. This meant that I would either have to host a managed service in their cloud or self-host it on a VM in the cloud of my choice (GCP). This was looking like a lot of work for something that I just wanted to try out. Since I already had a Postgres database running on Cloud SQL, I decided to explore the possibility of also using it for time series data.

Time Series Data in Postgres

You have probably heard of the plugin called timescaledb

that allows you to store time series data in Postgres. It is a great plugin that

adds a lot of functionality to Postgres, but again, due to its licensing,

it’s not possible to use it on a managed service like Cloud SQL. This meant that

I had to look into the native capabilities of Postgres to handle time series

data.

However, not all of my final implementation was native to Postgres since

pg_partman and pg_cron

were used. The difference is that both of these plugins are licensed under the

PostgreSQL License, which is very

permissive and allows for use in managed services like Cloud SQL.

Implementation

Creating the Tables

First step was to create the table that would hold the metrics.

CREATE TABLE "metrics" (

"metadata_id" BIGINT NOT NULL,

"timestamp" TIMESTAMP(3) NOT NULL,

"value" BIGINT NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT "metrics_pkey" PRIMARY KEY ("metadata_id","timestamp")

) PARTITION BY RANGE ("timestamp");

This table had to be as lightweight as possible, so I decided to only store

the metadata_id, timestamp, and value. The metadata_id is a foreign

key referencing the metrics_metadata table, which stores the dimensional

data (in my case, server and rule IDs). This normalization keeps the metrics

table lightweight since the dimensional data isn’t repeated for every

metric data point.

Why a composite primary key?

The primary key is a combination of (metadata_id, timestamp) rather than a

simple auto-incrementing ID. This serves two important purposes:

Ensures uniqueness: It guarantees that for any given dimension (identified by

metadata_id), there can only be one metric entry per timestamp. This prevents duplicate entries and ensures data integrity.Matches query patterns: All will filter by both

metadata_idto identify the rule andtimestampto match a time range. Having both fields in the primary key means they’re automatically indexed together in exactly the order queries need them.Efficient within partitions: After partition pruning eliminates irrelevant partitions based on the

timestamprange, the(metadata_id, timestamp)allows for fast lookups within the relevant partition(s).

CREATE TABLE "metrics_metadata" (

"id" BIGSERIAL NOT NULL,

"dimension_1" TEXT NOT NULL,

"dimension_2" TEXT NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT "metrics_metadata_pkey" PRIMARY KEY ("id")

);

Why a separate metadata table?

The metrics_metadata table acts as a lookup table that stores the unique

combinations of dimensional data. Instead of storing these text values

repeatedly in every single metrics row (which could be millions of records),

they’re stored once in the metadata table and referenced by ID.

For example, if you have dimensions that generate 10,000 metrics entries per

day, those dimension values are stored only once in metrics_metadata,

then that single metadata_id is referenced in all 10,000 metrics rows. This

significantly reduces storage space and improves query performance.

Design choices explained:

BIGSERIALvsBIGINT: Themetrics_metadatatable usesBIGSERIALfor itsidcolumn (auto-incrementing), whilemetricsusesBIGINTformetadata_id. This is becausemetadata_idis a foreign key that referencesmetrics_metadata.id, so it needs to match the data type but doesn’t need auto-increment functionality.No explicit foreign key constraint: You might notice that

metadata_idisn’t declared with aFOREIGN KEYconstraint. While foreign keys are supported on partitioned tables, they add complexity to partition management operations (like dropping partitions) and require additional lookups and locks on each INSERT. For this high-volume time series use case, enforcing referential integrity at the application level provides both better insert performance and operational flexibility.

Adding a Covering Index

Next, I created a covering index

on the metrics table to speed up queries that filter by metadata_id and

timestamp. This index allows me to quickly retrieve the metrics for a

specific dimension over a given time range.

The trick here is to use the INCLUDE clause to include the value column

in the index, which allows avoiding table data access for queries

that only need the metadata_id, timestamp, and value columns.

CREATE INDEX "metrics_metadata_id_timestamp_key"

ON "metrics"("metadata_id", "timestamp")

INCLUDE ("value");

Setting Up Partitioning

While I declared the table as partitioned with PARTITION BY RANGE ("timestamp"), I hadn’t actually created any partitions yet. This is where

pg_partman comes in. It automates the creation, management, and deletion of

partitions over time.

Without pg_partman, I would need to manually create each partition using

SQL like:

CREATE TABLE metrics_p2026_w07 PARTITION OF metrics

FOR VALUES FROM ('2026-02-17') TO ('2026-02-24');

And repeat this for every week, then manually drop old partitions when they’re

no longer needed. pg_partman handles all of this automatically.

The following SQL script sets up pg_partman to manage the partitioning for

the metrics table:

CREATE SCHEMA partman;

CREATE EXTENSION pg_partman SCHEMA partman;

-- Create partitioning for metrics table using pg_partman

SELECT partman.create_parent(

p_parent_table := 'public.metrics',

p_control := 'timestamp',

p_interval := '1 weeks',

p_premake := 4

);

-- Configure retention

UPDATE partman.part_config

SET retention = '4 weeks',

retention_keep_table = false,

retention_keep_index = false

WHERE parent_table = 'public.metrics';

-- Create initial partitions

SELECT partman.run_maintenance('public.metrics');

Where:

p_interval := '1 weeks': Creates a new partition for each week. This means that data for each week will be stored in its own physical partition, making queries that filter by time range much faster since Postgres can skip entire partitions that don’t match the time range.p_premake := 4: Automatically creates 4 partitions ahead of time. This ensures that when new data arrives, there’s always a partition ready to receive it without any performance hiccups from creating partitions on-the-fly.retention := '4 weeks': Automatically drops partitions older than 4 weeks. This is important for managing disk space since I only need to keep up to 4 weeks of metrics data. Older data will be automatically removed without needing to run manualDELETEqueries, which can be inefficient and leave behind fragmented tables.retention_keep_table := false: When dropping old partitions, completely removes them instead of just detaching them. This ensures the disk space is actually freed up.

Automating Partition Maintenance

Finally, I set up automatic maintenance using pg_cron

to ensure partitions are managed automatically:

CREATE EXTENSION pg_cron;

SELECT cron.schedule(

'partman_maintenance',

'0 8 * * *',

'SELECT partman.run_maintenance()'

);

This cron job runs daily at 8 AM and takes care of:

- Creating new partitions ahead of time (based on

p_premake) - Dropping old partitions that exceed the retention period

- Ensuring indexes are properly maintained across all partitions

Summary

With this setup, I was able to store and query time series metrics efficiently without needing a dedicated time series database. The partitioning should keep queries fast by limiting the amount of data Postgres needs to scan, and the automatic retention management ensures I won’t accumulate unnecessary historical data.

Expected benefits:

- Fast queries: Partition pruning allows Postgres to skip entire partitions that don’t match the time range

- Efficient data deletion: Dropping old partitions is instant and doesn’t

leave behind fragmented tables like

DELETEstatements would - Predictable storage: With automatic 4-week retention, disk usage should stay constant and predictable

- Index-only scans: The covering index on

(metadata_id, timestamp) INCLUDE (value)should allow queries for a specific dimension’s metrics over time to be satisfied entirely from the index without touching the main table data

For my use case, this approach offers a good balance between functionality and simplicity. It makes use of Postgres features available on Cloud SQL without the complexity or cost of managing a separate time series database.

While I haven’t yet deployed this to production, the design follows established patterns for time series data in PostgreSQL and should scale well for moderate workloads.